Sharing Our Loss and Grief

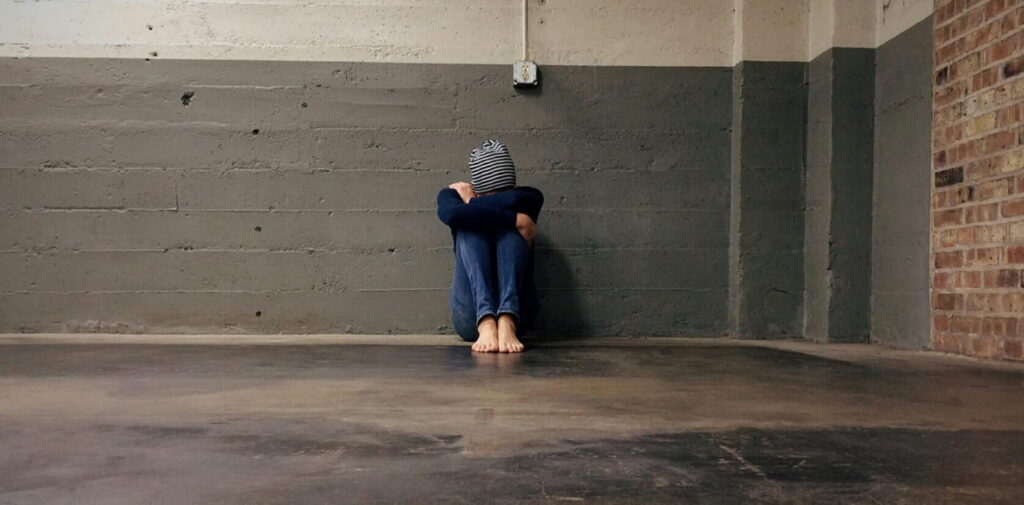

There are times when the crushing weight of grief threatens to break us—when it feels as though our minds are unraveling

I Had No Choice When My Father Died.

I had no choice when my father died. People often tell me, “Wow, you are so strong. I never knew you lost your father when you were so young.” How many times have we heard those words as adults? Too many to count. Each time, those words hit with the weight of unseen scars. They echo not only the surprise at our endurance, but also the silent suffering we carry—an ache that no amount of so-called strength can truly mend. We never aspired to be strong. Strength was forced upon us by relentless circumstance—a burden we inherited long before we could even spell the word “resilience.” It is not a heroic trait we were born with, but a desperate adaptation we cultivated to survive the kind of devastation that shatters innocence. As children, staring blankly at the concept of death, we grew resilience the way trees sprout through cracked concrete: slow, battered, and utterly alone. Losing your parent is a wound that never truly closes, no matter your age. They are the ones who gave you life, who shaped you from the very first heartbeat. Their presence is woven into your DNA, their love carved into your soul. The bond between parent and child is more than biological—it is primal, sacred, and essential. As infants, we desperately relied on them to survive. Our parents were our protectors, our haven in a bewildering universe, standing between us and every threat until we could learn to stand on our own. But what happens when a father or mother dies when you are only three months old, or five years of age, or thirteen? You do not just lose a parent. You lose the guiding star that was supposed to see you through the storms of childhood, the steady hand meant to lead you toward adulthood. The world suddenly becomes a dangerous, cold, unfamiliar place where safety and comfort dissolve overnight. Death is not just a distant shadow; it becomes a wall that slams into you before you have even learned to run and before life has revealed its miracles. You are forced to wander through a world stripped of the loving guidance, protection, and security so vital to growing into a healthy adult—left to piece together hope, dreams, and identity from the fragments of what should have been. Death arrested our healthy development, and grief has turned into a lifetime of longing. The absence of a parent is a daily ache, a silent grief that stretches across all the milestones: graduating, stepping onto a college campus, walking down the aisle, welcoming your own children, facing heartbreak and triumph. Their absence is a shadow that follows us through every major event of our lives, a constant reminder of what was stolen, the celebrations that will always be marked by a missing face in the crowd. Our grief is not fleeting, it is a lifelong companion, as constant as our heartbeat, growing up alongside us and lingering until our final days. For those who lost a loved one too soon, grief becomes a silent shadow, creeping into every corner of our lives. It is the only way our love for our dead parents continues to exist. Prolonged grief shapes us—complex, terrifying, brutal, silent, hidden from view. It evolves as we grow, often buried deep beneath the surface because facing its magnitude was too much. Like a dormant volcano, it erupts when our strength finally runs dry, when our bodies can no longer contain the pain. And as we gain the capacity to sit with loss, it does not become easier. In fact, the pain can intensify, growing sharper after years of silent suppression. Losing a parent at an early age does not make us stronger; it simply forces us to endure what should never have been asked of us. Accepting life without our parent comes at a brutal cost—loneliness, PTSD, waves of depression and anxiety, struggles in forming healthy relationships. Yes, we barely made it into adulthood, but the price was a toll that no child should ever be required to pay. The tragedy is not just in the loss, but in the lifelong echo of that absence—and in the heartache that we carry, always. Can you recall people feeling pity for you? Share your story in the comments! 2 Comments KirstenJanuary 6, 2026 at 2:45 pm | Edit Beautifully written. We were so young and so unprepared. Death shouldn’t have been anywhere near our radar, but we were forced to become familiar with something so final. I don’t recall the reactions of others. I think most of the outward attention was on my mum, but I’m sure people did feel for us. They perhaps just didnt know what to do or say so hoped we’d get over it. As you say, though, this is a grief that never leaves you( and never, I think, really diminishes) Kirsten x Reply Hissi AlemJanuary 10, 2026 at 8:12 pm | Edit I had a similar experience, Kirsten. The attention was on my grieving mom. I do think that adults might have a hard time addressing a child’s way of grieving. “What are the right words to say?”, is what probably is on their minds. And yes, it is a grief that never leaves us because our loss single-handedly changed the trajectory of our lives. Reply Leave a Reply Cancel reply Logged in as saleem@prismpixel.com. Edit your profile. Log out? Required fields are marked * Message* Δ

Healing and Grieving

Healing isn’t just a process, it is a journey that stretches across a lifetime, much like the endless path of grieving.

Healing From Childhood Neglect-Inner Child Meditation

Many of us, as children, found ourselves in a storm of anxiety, confusion, and isolation after the heartbreaking loss of our parents.

To My Daddy in Heaven

I never asked to be this strong—

never wished for courage forged by surreal loss,

A gravity impossible to ignore

A gravity impossible to ignore Today, October 6th, weighs on me with a gravity that is impossible to ignore. There is a heaviness in my chest, a subdued ache that settles into my bones—today is a day that always returns, no matter how much time has passed. This afternoon, I found myself sitting in the pulmonologist’s office, discussing the next steps in managing my sleep apnea. My compassionate doctor checked my CPAP machine, encouraged me for the progress I’ve made, and spoke patiently about the importance of sleep hygiene. But as he spoke, my mind drifted—caught in a tapestry of memory and longing. The irony never escapes me: my father’s life was cut short by a cruel lung disease, Pulmonary Hypertension, and here I am, decades later, sitting in a clinic surrounded by the advances that might have given him a different future, a future we will never know. The world has changed so much, medicine has leaped forward, but the past remains untouchable and irreversible—a wish that aches with its impossibility. This day marks the final hours I would ever have with my father. I remember it with a clarity that is both a blessing and a curse—the day before he was taken from us, sent away by ambulance, never to return home. It was in those fragile hours of October 7th, 1986, at 4:30 AM, that the phone rang, shattering our lives. We rushed to the hospital, desperate and unprepared, only to be met with the kind of news that splits a life into “before” and “after.” That morning, before the sun painted the sky, my childhood ended with a single phone call and my mother’s piercing screams. Thirty-nine years have passed, and still, the ripples of that moment are felt in every corner of my being. The older I become, the more I feel the depth and weight of his absence—it’s as if grief has woven itself into every cell, demanding my surrender, claiming space in my body, soul, and mind. Grief has never left me. It has always been with me. Our grief, the grief of adults who lost a parent as children, is a journey through shifting landscapes—it is invisible and silent at first, then grows in force and clarity as we pass from one phase of life to the next. There is no expiration date on our sorrow. We carry it through every milestone, every joy and disappointment, every quiet moment when we wish for a voice, a guiding hand, a father’s or mother’s embrace. Tonight, as darkness falls, I will honor my father. I will light a candle—maybe two—in his memory. I will speak his name, Alem Dellele Taffere, aloud to those I love, refusing to let the passing of years diminish the truth of my loss or the power of his presence in my life. Unlike in the past, I will not apologize for the tears that still come, or the longing that has not faded. My father, forever 36, lives on in the stories I tell, in the space he left behind, and in the love that refuses to yield to time. This grief is my inheritance, my companion, and the testament to a bond that not even death can erase. 2 Comments AidaOctober 7, 2025 at 10:44 am | Edit Mein Schatz, welch ein bitter-schöner Beitrag , wunderschön geschrieben. Ich wünschte ich hätte Deinen Papa kennengelernt. Ich drücke Dich und gedenke Deinen Papa ebenfalls mit einer Kerze Deine Aida Reply Hissi AlemNovember 8, 2025 at 9:21 pm | Edit oh mein Schatz, danke fuer deine lieben Worte! Reply Leave a Reply Cancel reply Logged in as saleem@prismpixel.com. Edit your profile. Log out? Required fields are marked * Message* Δ

When Grief Becomes Too Exhausting

There are days when grief is so overwhelming, it threatens to swallow me whole.

Hugging My Grieving Inner Child

Our inner child does not need to be scared any more but express the hidden grief in safety.

Grief So Deep

Grief so deep It feels like an ocean swallowing me whole, leaving me gasping for air. I want to scream, to tear through the walls around me, but no act of total desperation could ever bring you back. The ache of your absence is a raw tidal wave that crashes over me again and again. I cry tears I thought had dried long ago, and with each drop, I feel the sharp sting of loss. My heart, broken and weary, keeps beating only to remind me of the space you once filled. I am caught in this relentless storm, powerless against its fury. I would give anything—climb the highest peaks, battle the fiercest foes, or sacrifice every ounce of myself—if it meant holding you once more. Oh, how I miss you so much!! But grief does not grant wishes. It forces me to surrender, to let the pain wash over me, and to carry the weight of this sorrow. You are gone, and I am left with this aching love that will never fade; until the moment I fade. Leave a Reply Cancel reply Logged in as saleem@prismpixel.com. Edit your profile. Log out? Required fields are marked * Message* Δ

On Loss of Innocence

When death visits a family and claims a parent, a child’s innocence is lost forever.